While INCO (now Vale) was always the dominant player in the nickel mining and processing scene in Sudbury, Falconbridge (now Glencore) was the major independent competitor to INCO. This post will look at Falconbridge and how it relates to CPR’s railway operations.

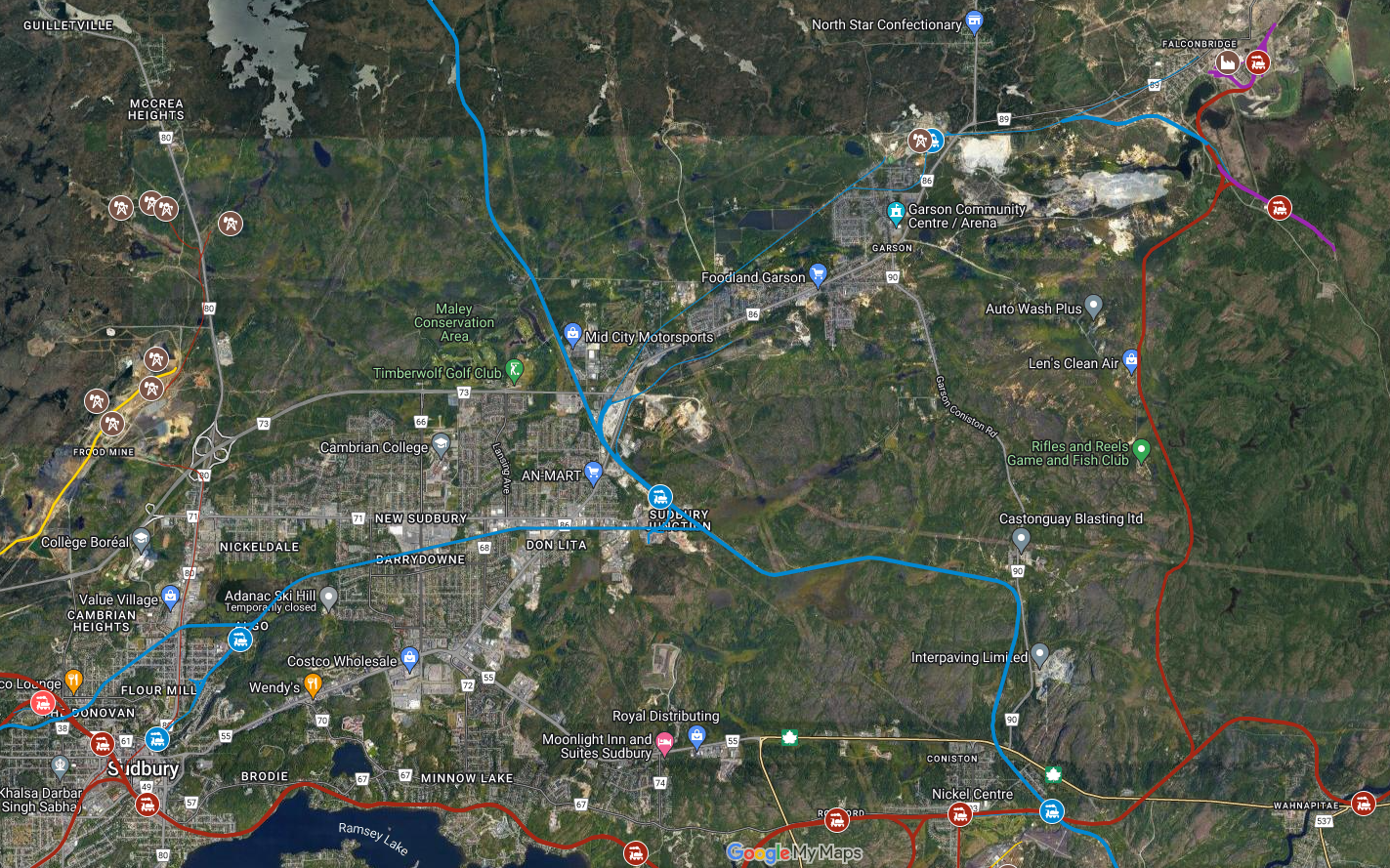

Map showing location of Falconbridge smelter (top right) and rail lines. Red lines are Canadian Pacific, blue lines are Canadian National.

Falconbridge Mine and Smelter

Falconbridge Nickel Mines Ltd. was incorporated in 1928 to develop mining claims near the village of Falconbridge to the north-east of Sudbury. The first mine on the site was brought into operation in 1930. At the same time, development of a mill and smelter adjacent to the mine site was begun, with the smelter beginning operation in 1930 and the concentrating mill in 1933. A second mine at Falconbridge opened in 1935.

Due to patent restrictions in North America on nickel refining processes, Falconbridge purchased the Nikkelverk Refinery in Kristiansands, Norway in 1929 to acquire access to the refining processes they required. The smelter in Ontario produced a semi-refined nickel product known as “matte”, which would be refined to cathodes in the Norway facility.

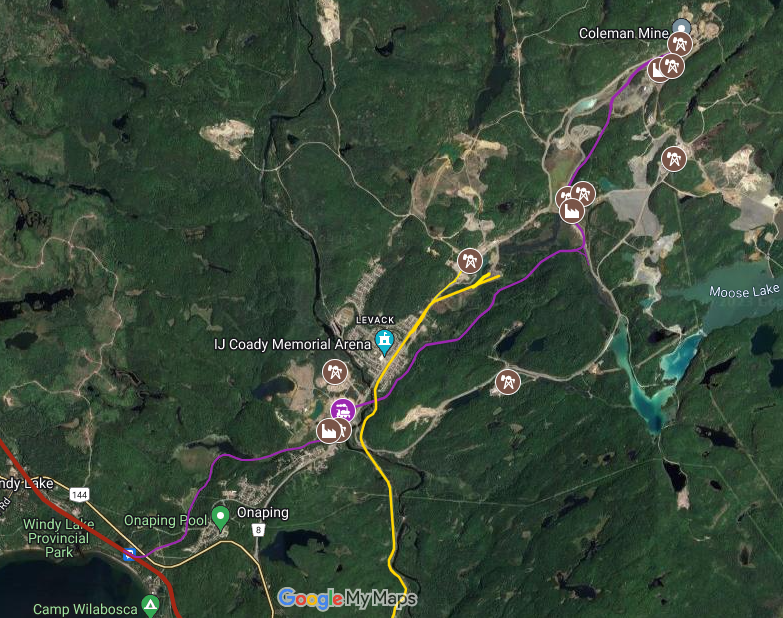

Rail map of the Onaping-Levack area. Red line at bottom left is the CPR main line. The (now-abandoned) FNM railway is in purple. Yellow is the INCO line to Levack Mine.

Hardy Mine/Mill

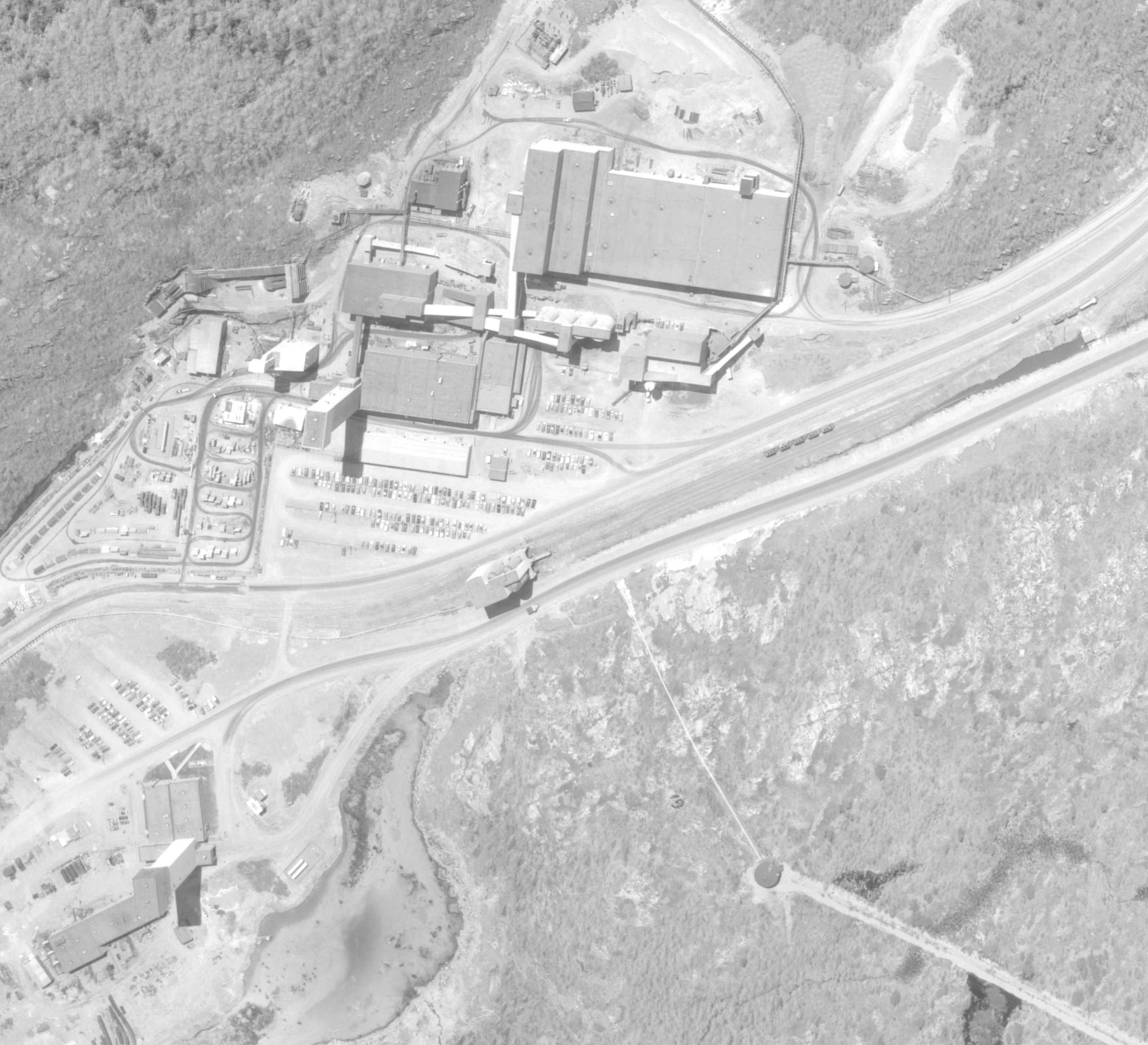

In the early 1950s, Falconbridge expanded their mining operations from their original mines on the east side of Sudbury and developed some mines on the north west rim of the Sudbury crater in the Onaping-Levack area. By 1955 these operations included a pair of nickel-copper mines, Hardy Mine and Mount Nickel Mine, and a processing mill (Hardy Mill) located alongside Hardy Mine on the south-west edge of the town of Levack, capable of processing 1,500 tons of ore per day into concentrate which would be shipped to the smelter at Falconbridge east of Sudbury in open cars (hoppers and gondolas). This dry concentrate has been described as “pyrophoric”, meaning it can spontaneously undergo oxidation reactions (combustion) in contact with air and/or moisture, and could arrive at the smelter in a clumped or “burning” state.

To serve the new mines and mill, a new private rail line was built between Hardy Mine/Mill to the CPR Levack siding where several interchange transfer tracks were built. FNM locomotives would haul loads from the mill to the CPR and bring back empties delivered by CP. Hardy Mill was FNM’s rail base of operations, with a single stall engine shop, repair track, and a turning wye located next to the mill loading tracks.

1975 aerial photo of Hardy mine and mill. City of Greater Subdury aerial imagery. (Click on image to open larger size)

The Hardy Mill operated until 1977 when it was closed, with the older mines in the area reaching end of life near the end of the 1970s, and newer replacement mines having their ore processed at the newer Strathcona Mill (see below).

Fecunis Mine/Mill

In 1956 a new pair of mines, the Fecunis and Longvack Mines were in development on the north-east side of Levack. The odd name of “Fecunis” is based on the chemical symbols of the primary minerals found in the rocks here – iron (Fe), copper (Cu), nickel (Ni), and sulphur (S). By 1957 these mines and a new mill at Fecunis to handle the production were on line capable of processing 2,400 tons per day of ore into concentrate, which like Hardy Mill was shipped in a partially dry concentrate in open cars. The FNM private rail line was extended past Hardy Mill to serve the new mill. Additionally another large mine, the Onaping Mine, was opened by the end of the 1950s.

Fecunis mine and mill aerial photo from 1975. City of Greater Sudbury aerial imagery. (Click on image to open larger size)

The Fecunis Mill closed operations in 1979.

Strathcona Mill

Also in 1956 the Strathcona Mine was discovered, though it would be 1967 before this mine went into full production along with a brand new mill which would serve as the basis for all further Falconbridge expansions in the Levack/Onaping area.

Strathcona mill Aerial 1975. City of Greater Sudbury aerial imagery. (Click on image to open larger size)

The new Strathcona mill opened in 1967 with a 6,000 tons per day capacity, but was upgraded quickly to 7,500 tons per day capacity to support increased production from various new mines in the area.

In contrast to the Hardy and Fecunis Mills, the concentrate produced at Strathcona Mill was shipped to the smelter in a slurry form, with the concentrate mixed with water. To handle this traffic, CP provided a small fleet of specially designed short cylindrical hoppers to carry the slurry from Strathcona to Falconbridge. The first 20 of these cars were built in 1967, with another 40 cars added in 1969. These cars operated to the late 1980s or early 1990s, as the cars were starting to wear out due to the rough effects of the concentrate slurry on the interiors of the cars. At this point, rail service to Falconbridge’s Levack operations came to an end, as Falconbridge elected to ship their product by truck rather than agree to CPR freight rates that would have covered replacement costs for the rail cars.

CP 381930 represents the special hoppers that were constructed for the slurry concentrate service from Strathcona Mill to Falconbridge. Bill Grandin Collection photo.

While no longer rail served, Strathcona Mill remains an important and active processing site for nickel ores from Glencore’s (Falconbridge’s current successor) mines in the area to this day.

Nickel-Iron Refinery

In 1970 Falconbridge opened a large new facility on their property on the south-east side of their main smelter to recover the trace amounts of iron from the processed nickel ores in order to directly market it to the steel industry. Unfortunately this operation was short-lived and closed in 1972.

Aerial photos from 1975 show a rather significant set of railway yard tracks and loading (and/or unloading) structures at this (then shuttered) facility, and CN (which also accessed the Falconbridge smelter via the north side) also built a spur crossing the CPR spur to directly access the iron plant. However given the short lived nature of this operation we have very little other information on its operation from a railway perspective; what went in and out by which railway and what kind of cars used.

Falconbridge Smelter Upgrades

Another major project at Falconbridge was the construction during the 1970s of an upgraded smelter using new modern technology. This modernization project opened in 1978. The project included new fluidized bed roasters which removed iron sulphide from the ore, and electric furnaces to smelt the roasted ore. The upgrade also included an acid plant which captured sulphur compounds from the off-gas of the roasters and produced large quantities of sulphuric acid. Some of the tracks leading to the shuttered iron plant (which was itself demolished) were reused to built large tank car loading racks for the sulphuric acid.

Railway Operations

Operations at Levack should have been fairly simple. While the exact operations of the FNM railway aren’t really documented, it seems Hardy Mine is their base of operations with a small engine shop and repair track. Operating from this base of operations, FNM switchers would gather up outbound loaded cars from the Hardy, Fecunis, and Strathcona Mills and deliver them to the CPR interchange tracks, pick up empties left by CP and spot them at the mills for loading. As noted in the individual descriptions of the mills above, Hardy and Fecunis mills loaded dry or semi-dry concentrate into open cars and Strathcona loaded a liquid slurry into special cylindrical hoppers. On the CP side, a local operating out of Sudbury yard would run up to Levack siding to deliver the empties and lift the loads left by FNM, which would then operate to the smelter where the loads would be dropped off in interchange tracks for the Falconbridge plant switchers.

After Hardy and Fecunis Mills closed (in 1977 and 1979 respectively), the trains from Levack to Falconbridge became “unit” trains of cylindrical slurry cars from Strathcona Mill. By the 1990s rail transport of concentrate from Strathcona was replaced by trucks ending FNM’s rail operations in Levack.

CP-FNM interchange tracks at Falconbridge smelter site. Note that a CP track is actively performing an interchange here (locos and caboose visible at left.) This shot gives a good overview of the traffic between Onaping and Falconbridge, showing a mix of open cars of dry concentrate, and the distinctive little short slurry cars from Strathcona. At bottom right the FNM switcher appears to also be lifting or spotting covered hoppers probably for nickel matte. (Click on image to open larger size)

Outbound traffic from the smelter was in the form of powdered nickel matte. Due to patent restrictions on refining processes in North America, the matte was shipped to the Falconbridge owned refinery in Kristiansands, Norway for refining. Originally the matte was shipped out of the smelter in barrels, but changed to bulk shipments in covered hopper cars in 1968. As both CN and CP had rail access to the Falconbridge smelter, it’s a little unclear how much product went out via each railway during the 1970s. By the 1990s, CN had abandoned their spur line to Falconbridge and contracted a switching arrangement with CP, wherein CN would supply cars via the interchange at CN Junction between Sudbury and Copper Cliff and CP would exclusively switch the plant.

CP local heading up the spur track to Falconbridge in the late 1990s. The train consists mainly of CN hoppers for nickel matte loading (as CN had abandoned their access to Falconbridge by this time and engaged in a switching agreement with CP) and tank cars for sulphuric acid. By this point rail moves of ore concentrate to the smelter had ended. WRMRC collection.

After the new plant upgrades in 1978, sulphuric acid also became a major outbound commodity; with again CN and CP both having direct access to the acid loading tracks until CN’s abandonment of their line to Falconbridge, making it hard to know how much traffic was split between the two railways.

After the 1978 electric furnace upgrade, coke was used as an input. This was sourced from the US and we have noted the occasional presence of various hoppers from the Eastern Seaboard in Sudbury yard in some late seventies photos. An additional input to the mill was powdered dolomite or limestone, which mostly arrived in Penn Central/Conrail covered hoppers.

After the late 1970s upgrade, separate locals handled the ore concentrate from the Levack region and the acid/coke/dolomite/matte traffic to the smelter.

Equipment

Diesel locomotives operated by Falconbridge consisted of a small collection of ALCO/MLW S-series switchers and GE centre-cab models. The larger ALCO and GE 80-ton units seem to have seen service at either Falconbridge or Levack, while the smaller 45 ton models were probably exclusively used within the Falconbridge smelter complex.

Falconbridge S-4 #108, built new for Falconbridge in 1955, showing its 1970s era paint scheme. At CP’s Sudbury shops for maintenance or transfer between FNM operations.

| No. | Builder | Date | Model | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | ALCO | 5/49 | S-2 | ex-NW 3321, ex-Wabash 321; to FNM 3/71 |

| 103 | ALCO | 12/46 | S-1 | ex-EL 309, ex-ERIE 309; to FNM ?/66 |

| 104 | GE | 8/26 | 45 ton | New |

| 105 | GE | 1/48 | 45 ton | New; fire damaged 3/71, sold |

| 106 | GE | 12/51 | 80 ton | New |

| 107 | GE | 4/53 | 80 ton | New |

| 108 | MLW | 7/55 | S-4 | New |

| 109 | MLW | 1/50 | S-4 | ex-Canadian Commercial #1, to FNM /68 |

In terms of freight equipment, Falconbridge would have operated the usual assortment of hot-metal and slag cars for intra-plant movements within the smelter complex, and other freight equipment for the shipment of ores and concentrates from the Levack operation and shipment of refined products out from the smelter were provided by CN and CP.